It’s a shame that so many organisations rely on HTTP basic-auth and self-signed certs to secure access to internal tools. Sure enough, it’s quick and easy to deploy, but you get stuck in a world where:

- Credentials are scattered and difficult to manage

- The usability of some tools gets broken

- Each person coming in or out of the company means

either a sweep of the your password databases or a new attack surface.

The only plausible cause for this state of affairs is the perceived complexity of setting up an internal PKI infrastructure. Unfortunately, this means passing out on a great UI-respecting authentication and - with a little plumbing - authorization scheme.

Once an internal CA is setup you get the following benefits:

- Simplified securing of any internal website

- Single-Sign-On (SSO) access to sites

- Easy and error-free site-wide privilege revocation

- Securing of more than just websites but any SSL aware service

Bottom line, CAs are cool

The overall picture of a PKI

CAs take part in PKI - Public Key Infrastructure - A big word to designate a human and/or automated process to handle the lifecycle of digital certificates within an organisation.

When your browser accesses an SSL secured site, it will verify the presented signature against the list of stored CAs it holds.

Just like any public and private key pairs, the public part can be distributed by any means.

The catch

So if internal CAs have so many benefits, how come no one uses them ?

Here’s the thing, tooling plain sucks. It’s very easy to get lost in

a maze of bad openssl command-line options when you first tackle the

task, or get sucked in the horrible CA.pl which lives in

/etc/ssl/ca/CA.pl on many systems.

So the usual process is: spend a bit of time crafting a system that generates certificates, figure out too late that serials must be factored in from the start to integrate revocation support, start over.

All this eventually gets hidden behind a bit of shell script and ends up working but is severely lacking.

The second reason is that, in addition to tooling issues, it is easy to get bitten and use them the wrong way: forgot to include a Certificate Revocation List (CRL) with your certificate ? You have no way of letting your infrastructure know someone left the company ! You’re not monitoring the expiry of certificates ? Everybody gets locked out (usually happens over a weekend).

A word on revocation

No CA is truly useful without a good scheme for revocation. There are two ways of handling it:

- Distributing a Certificate Revocation List (or

CRL), which is a plain list of serials that have been revoked. - Making use of a Role Based Access Control (or

RBAC) server, which lives at an address bundled in the certificate which clients can connect to to validate.

If you manage a small number of services and have a configuration management framework or build your own packages, relying on a CRL is valid and will be the mechanism described in this article.

The ideal tool

Ultimately, what you’d expect from a CA managing tool is just a way to get a list of certs, generate them and revoke them.

Guess what ? Chances are you already have an internal CA !

If you manage your infrastructure with a configuration management framework - and you should - there’s a roughly 50% chance that you are using puppet.

If you do, then you already are running an internal CA, since that is what the puppet master process is using to authenticate nodes contacting it.

When you issue your first puppet run against the master, a CSR

(certificate signing request) is generated against the master’s CA,

depending on the master’s policy it will be either automatically signed

or stored, in which case it will show up in the output of the

puppet cert list command. CSRs can then be signed with

puppet cert sign.

But there is nothing special to these certificates, puppet cert just

exposes a nice facade to a subset of OpenSSL’s functionality.

What if I dont' use puppet

The CA part of puppet’s code stands on it’s own and by installing puppet

through apt-get, yum, or gem you will get the functionality

without needing to start any additional service on your machine.

Using the CA

Since your CA isn’t a root one, it needs to be registered wherever you will need to validate certs. Usually this just means installing it in your browser. The CA is nothing more than a public key and can be distributed as is.

For the purpose of this article, puppet wil be run with a different

configuration to avoid interfering with its own certificates. This means

adding a --confdir to every command you issue.

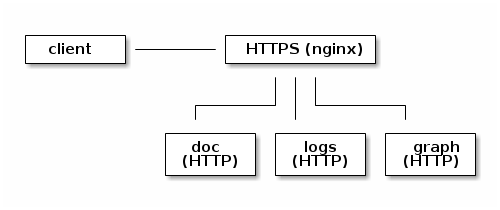

A typical set-up

To illustrate how to set up a complete solution using the puppet commmand line tool, we will assume you have three separate sites to authenticate:

- Your internal portal and documentation site:

doc.priv.example.com - Graphite:

graph.priv.example.com - Kibana:

logs.priv.example.com

This set-up will be expected to handle authentication on behalf of graphite, the internal portal and kibana.

Although a CA can be published to several servers, in this mock infrastructure, a single nginx reverse proxy is used to redirect traffic to internal sites.

Setting up your CA

First things first, lets provide an isolated sandbox for puppet to handle its certificates in.

I’ll assume you want all certificate data to live in /etc/ssl-ca.

Start by creating the directory and pushing the following

configuration in /etc/ssl-ca/puppet.conf

[main]

logdir=/etc/ssl-ca/log

vardir=/etc/ssl-ca/data

ssldir=/etc/ssl-ca/ssl

rundir=/etc/ssl-ca/run

Your now ready to generate your initial environment with:

puppet cert --configdir /etc/ssl-ca list

At this point you have generated a CA, and you’re ready to generate new certificates for your users.

Although certs can be arbitrarily named, I tend to stick to a naming

scheme that matches the domain the sites it runs on, in this case,

we could go with users.priv.example.com.

We have three users in the organisation: Alice, Bob and Charlie, lets give them each a certificate and one for each service we will run.

for admin in alice bob charlie; do

puppet cert --configdir /etc/ssl-ca generate ${admin}.users.priv.example.com

done

for service in doc build graph; do

puppet cert --configdir /etc/ssl-ca generate ${service}.priv.example.com

done

Your users now all have a valid certificate. Two steps remain: using the CA on the HTTP servers, and installing the certificate on the users' browsers.

For each of your sites, the following SSL configuration block can be used in nginx:

ssl on;

ssl_verify_client on;

ssl_certificate '/etc/ssl-ca/ssl/certs/doc.priv.example.com.pem';

ssl_certificate_key '/etc/ssl-ca/private_keys/doc.priv.example.com.pem';

ssl_crl '/etc/ssl-ca/ssl/ca/ca_crl.pem';

ssl_client_certificate '/etc/ssl/ssl/ca/ca_crt.pem';

ssl_session_cache 'shared:SSL:128m';

A few notes on the above configuration:

ssl_verify_client oninstructs the web server to only allow traffic for which a valid client certificate was presented.- read up on

ssl_session_cacheto decide which strategy works for you. - do not be fooled by the directive name,

ssl_client_certificatepoints to the certificate used to authenticate client certificates with.

Installing the certificate on browsers

Now that servers are ready to authenticate incoming clients, the last

step is to distribute certificates out to clients. The ca~crt~.pem and

client cert and key could be given as-is, but browsers usually expect

the CA and certificate to be bundled in a PKCS12 file.

For this, a simple script will do the trick, this one would expect the name of the generated user’s certificate and a password, adapt to your liking:

#!/bin/sh

name=$1

password=$2

domain=example.com

ssl_dir=/etc/ssl-ca/ssl

cert_name=`echo $name.$domain`

mkdir -p $ssl_dir/pkcs12

openssl pkcs12 -export -in $ssl_dir/certs/$full_name.pem -inkey \

$ssl_dir/private_keys/$full_name.pem -certfile $ssl_dir/ca/ca_crt.pem \

-out $ssl_dir/pkcs12/$full_name.p12 -passout pass:$password

The resulting file can be handed over to your staff who will then happily access services

Handling Revocation

Revocation is a simple matter of issuing a puppet cert revoke command

and then redistributing the CRL file to web servers. As mentionned

earlier I would advise distributing the CRL as an OS package, which will

let you quickly deploy updates and ensure all your servers honor your

latest revocation list.